By Jeremy Newhouse, Head of AI Delivery

I have used Artificial Intelligence (AI) to write code that scales to levels of complexity I do not fully understand. Software is getting easier to produce—and harder to own.

That’s not a contradiction; it’s the core tension I see on almost every engagement. Modern AI coding tools can generate working code at astonishing speed. But scalable software isn’t measured by how quickly you can create code. It’s measured by how reliably you can change it later: under load, under audit, under incident pressure, and under client handoff constraints.

Here is the workflow I’ve seen consistently separate “AI helped us ship” from “AI helped us ship — a mess.” It’s rooted in lessons that go back to the original “software crisis” and updated for agentic coding workflows (Claude Code, Codex, and similar). The punchline is simple:

Use AI to scale understanding and discipline—not just output.

—

The software crisis never ended; it just changed shape

The term “software crisis” is commonly traced to the late 1960s, when large systems were missing deadlines, overrunning budgets, failing requirements, and becoming unmaintainable. The 1968 NATO Software Engineering Conference is often cited as defining moment in naming the problem, even coining “software engineering” as a discipline in response.

What’s striking is how familiar the underlying complaint still sounds. We keep building systems that exceed our ability to fully reason about them. Dijkstra’s famous reflection captures the pattern: We didn’t arrive in an “eternal bliss” where all problems were solved, we found ourselves up to our necks in the crisis.

We responded with waves of leverage, including:

- higher-level languages

- structured programming, then OOP

- frameworks and patterns

- cloud, microservices, platform engineering

- and now: AI-assisted and agentic coding

Each wave increases what teams can attempt. And each wave tempts teams to attempt more than their processes can sustain. AI is simply the latest — and most powerful — amplifier.

The distinction that matters with AI: simple vs complex, easy vs difficult

If you want scalable software, you need one mental model nailed down early:

- Simple vs. complex describes the structure of a system (objective).

- Easy vs. difficult describes the effort required for _you_ to do something (subjective).

Rich Hickey’s Simple Made Easy is the cleanest articulation of this split I’ve seen.

AI pushes hard on the “easy” axis. You can ask for a feature and get hundreds or thousands of lines back in seconds. That’s easy. But that ease often comes with a hidden cost: complecting the system—interweaving logic, assumptions, and edge cases across boundaries until the design becomes complex.

In practice, this is what I call the speed/understanding inversion: code generation can outpace human comprehension. And when comprehension loses, scalability loses.

Why “it works” is a trap in production software

Most teams can get AI-generated code to work in a demo. The real question is whether the system will survive any number of real-life scenarios, from a new team inheriting it to a late requirement change to a performance incident or security review to a six-month migration or a client asking, “why did we do it this way?”

This is where Fred Brooks’ No Silver Bullet still matters. Brooks argues that much of software’s difficulty is essential: complexity is often inherent to the domain, not something you can wish away with a tool.

AI can absolutely shave off accidental complexity — boilerplate, mechanical refactors, repetitive glue code. But if you let AI generate architecture via conversational drift, you’ll manufacture accidental complexity at scale, faster than your team can pay it down.

So the goal isn’t “AI writes more code.”

The goal is “AI helps us write less code, with clearer boundaries.”

Agentic coding changed the game: from autocomplete to delegated execution

We’re moving from AI-as-suggester to AI-as-actor.

Tools like Claude Code position themselves as terminal-first, agentic assistants that help turn requests into code changes more directly than IDE autocomplete.

OpenAI Codex frames itself as a software engineering agent that can take on tasks like building features, fixing bugs, and proposing pull requests, often in parallel, in sandboxes.

Regardless of vendor, the workflow shift is the same: you’re no longer prompting for snippets; you’re delegating chunks of work.

That delegation is where teams either scale… or spiral.

A lot of the recent “vibe coding” conversation is essentially a warning about unstructured delegation: quick conversational iteration that feels productive but produces fragile systems if you don’t introduce constraints.

So what constraints actually work?

My operating model: Research → Planning → Implementation (and the gates between them)

In consulting, we don’t optimize for a single team shipping once. We optimize for:

- repeatability across environments

- usability for downstream teams

- and handoff stability for clients

That requires an artifact-driven approach: decisions and intent must be legible outside the head of the original developer (human or AI).

Here’s the workflow we use with AI so we get speed and long-term maintainability:

Phase 1: Research (AI as a system cartographer)

Intent: understand the current system before proposing a solution.

This is where AI can be genuinely superhuman: repository scanning, dependency tracing, summarizing call paths, and assembling a “what’s going on here” brief.

What I ask an agent to produce in Research:

- component and dependency map

- critical execution paths

- data lifecycle: where it’s created, transformed, stored

- existing constraints: auth boundaries, PII, latency/SLOs

- “if we change X, what breaks?”

Deliverable: a short Research Brief that a human can review quickly.

If you skip this phase, you don’t just risk coding the wrong thing, you risk encoding your misunderstanding into the architecture.

Phase 2: Planning (AI as spec writer + risk analyst)

Intent: reduce ambiguity into boundaries.

This is where we force hard questions. What is the smallest coherent design that solves the requirement? What contracts are we creating (APIs, events, data schemas)? What are the failure modes and rollback paths? What do we need to observe in production?

We capture this in artifacts that survive handoff:

- ADR (Architecture Decision Record): what we chose and why

- API/contract spec: request/response, errors, versioning

- data model changes: migrations + rollback plan

- non-functional requirements: performance, security, reliability

- test strategy: what we’ll prove and how

- observability plan: dashboards/alerts/traces

The point is not bureaucracy. It’s compression: turning a sprawling space of possibilities into a reviewable blueprint.

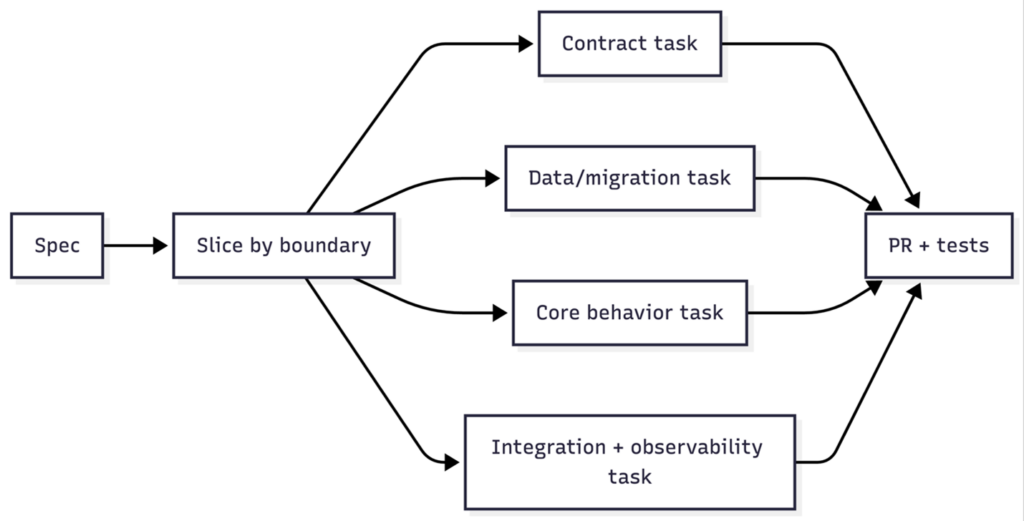

Phase 3: Tasking (the most underrated scalability lever)

Before the AI writes code, we slice the plan into tasks that respect boundaries.

This is how you avoid “AI did everything everywhere.”

A good task touches one primary component boundary, has a crisp definition of done, includes tests and docs expectations, and can be reviewed in under 15 minutes.

This is where consulting teams win: we design tasks for handoff clarity. If the client’s team needs to own this system after we leave, the task structure becomes their roadmap.

Phase 4: Implementation (AI as an execution engine per task)

Only now do we let agentic tooling loose.

For each task, we provide the relevant spec excerpt, repository conventions (style, lint, patterns), acceptance tests or examples, and explicit non-goals (“do not refactor unrelated modules”).

Then we let the agent implement that task, with tests.

This style fits agentic tools well—Claude Code in the terminal, Codex locally/in cloud workflows—without turning the repository into a reflection of a long chat.

The review gates that make AI scale safely

When code is cheap, the scarce resource becomes judgment.

So we institutionalize gates where human judgment is mandatory—and where AI can assist but not decide.

Gate 1: Architectural coherence

Questions:

- Did we introduce new concepts unnecessarily?

- Are boundaries cleaner or more tangled?

- Did we add “cleverness” where a boring pattern would do?

Gate 2: Contract integrity

Questions:

- Are APIs versioned appropriately?

- Are error modes explicit?

- Are we breaking downstream consumers?

Gate 3: Security and compliance

Questions:

- Are we handling PII correctly?

- Do we have authorization checks at the right layer?

- Did we introduce risky dependencies?

Gate 4: Test sufficiency

Questions:

- Are we testing behavior, not implementation details?

- Do we cover edge cases and regressions?

- Do we have a realistic integration test path?

Gate 5: Production readiness + observability

Questions:

- Can we detect failure quickly?

- Can we roll back safely?

- Do we have runbooks for known failure modes?

These gates aren’t anti-AI. They’re the mechanism that lets you use AI aggressively without waking up six months later in a new crisis.

—

The scalability challenges of AI-generated software (and what we do about them)

1) Context explosion

As systems grow, the relevant context for any change becomes harder to gather. Agentic tools help, but they also raise the risk of sweeping, cross-cutting edits.

Mitigation:

- task boundaries

- explicit file/module scope

- “allowed to change” lists

- staged PRs

2) Coherence drift (the silent killer)

Multiple AI-generated contributions can create inconsistent patterns: three ways to handle errors, four auth styles, five naming conventions.

Mitigation:

- repository conventions as first-class artifacts

- consistent PR templates

- a “house style” enforced by lint + review

3) False confidence

AI can produce plausible code that passes tests but is subtly wrong under production conditions. Brooks’ warning still applies: tools don’t remove essential complexity.

Mitigation:

- property-based tests where appropriate

- chaos/latency testing for critical services

- explicit invariants in code + docs

4) Handoff fragility

In consulting, “done” means the client can run, change, and debug it. AI makes it tempting to skip documentation because “the model can explain it later.” That’s not a real handoff.

Mitigation:

- ADRs and specs are part of “definition of done”

- runbooks and operational playbooks

- a 30–60 minute handoff walkthrough using artifacts, not vibes

Practical prompts I use (the ones that lead to scalable outcomes)

Research

- “Map the request path for X; list the modules and what each does.”

- “Where is the business logic for X located? Where should it live?”

- “Summarize data flow and identify where PII appears.”

Planning

- “Propose 2–3 designs; compare tradeoffs and failure modes.”

- “Write an API spec with errors and versioning assumptions.”

- “List risks and how we’ll detect issues in production.”

Tasking

- “Break this plan into 6 PR-sized tasks. Each should be reviewable in 15 minutes.”

- “For each task, define acceptance criteria and test expectations.”

Implementation

- “Implement Task 2 exactly. Do not refactor unrelated modules.”

- “Add tests that prove the behavior and protect against regressions.”

- “Update docs/runbook entries relevant to this change.”

If you do nothing else, do this: **force the agent to work inside boundaries you can review.**

What I tell clients adopting AI coding tools

If you’re adopting Claude Code, Codex, or similar, you don’t need a “tool rollout.” You need a workflow upgrade:

- Separate research, planning, and implementation

- Require specs and ADRs for anything that matters

- Slice work into bounded tasks

- Add review gates where humans own judgment

- Produce handoff artifacts as part of delivery

That’s how you turn AI from a code firehose into a scalable engineering system.

Closing: the new competitive advantage is disciplined simplicity

AI makes it easier than ever to build something. The winners will be the teams who can build something that survives change because they use AI to drive toward simple systems, even when that’s difficult.

The software crisis was never about a lack of code. It was about a lack of methods to manage complexity at scale. The opportunity now is to let AI shoulder the mechanical work while we double down on the timeless craft: boundaries, clarity, and judgment.

Need help with AI? Reach out to evolv.

Jeremy Newhouse is the Head of AI at evolv Consulting, where he leads the firm’s end-to-end AI capability—from strategy and solution architecture to hands-on AI engineering and delivery execution. Jeremy is especially strong in building modern AI systems in the real world, including AI platforms, GenAI/LLM applications, agentic workflows (multi-agent systems), and innovation accelerators that help clients move from experimentation to production outcomes faster. Based in the Dallas–Fort Worth area, he’s known for pairing executive-level advisory with a builder’s mindset—creating repeatable delivery patterns, prototypes, and go-to-market assets that elevate quality and speed across engagements. Previously, Jeremy was Head of Data & Analytics Products at Cognizant, leading global teams and data products that delivered measurable value through major performance improvements, meaningful efficiency gains, and risk reduction across enterprise analytics initiatives. He’s also a founder: as CEO and Founder of Salient Data, he launched AI-first platforms and agentic process automation solutions, bringing entrepreneurial product thinking and innovation leadership into his consulting practice. Jeremy holds an educational foundation in Software Engineering, has completed extensive graduate-level work and executive training in Data & Analytics and AI, and is a named inventor on a patent in large-scale risk analytics.